To download the schedule as one file click here.

To download the schedule as one file click here.

OBJECTS OF AFFECTION:

OBJECTS OF AFFECTION:

TOWARDS A MATERIOLOGY OF EMOTIONS

Princeton Conjunction – 2012. An Annual Interdisciplinary Conference

Serguei Oushakine (Slavic Languages and Literatures; Anthropology, Princeton U)

Anna Katsnelson (Slavic Languages & Literatures, Princeton U)

David Leheny (East Asian Studies, Princeton U)

Anson Rabinbach (Department of History, Princeton U)

Gayle Salamon (Department of English, Princeton U)

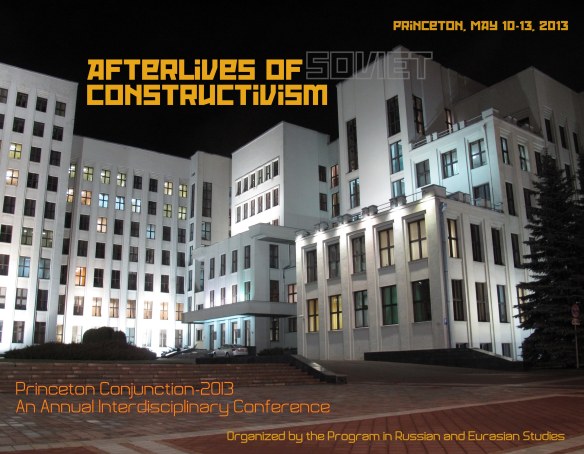

Princeton Conjunction – 2013: An Annual Interdisciplinary Conference

PRINCETON INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL AND REGIONAL STUDIES

PROGRAM IN RUSSIAN AND EURASIAN STUDIES

“ILLUSIONS KILLED BY LIFE”:

AFTERLIVES OF (SOVIET) CONSTRUCTIVISM

May 10-12, 2013

Princeton

Program Committee:

Serguei Oushakine (Princeton University), Chair;

Esther da Costa Meyer (Princeton University);

Kevin M.F. Platt (University of Pennsylvania);

Stephen Harris (University of Mary Washington);

Irina Sandomirskaja (Södertörns Högskola).

Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies;

Program in Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies

ROMANTIC SUBVERSIONS OF SOVIET ENLIGHTENMENT:

Questioning Socialism’s Reason

Serguei Oushakine, Chair (Princeton University)

Marijeta Bozovic (Yale University)

Helena Goscilo (The Ohio State University)

Mark Lipovetsky (The University of Colorado at Boulder)

Vera Tolz-Zilitinkevic ( The University of Manchester)